The Interborough Express Might Be NYC’s Best Transit Investment in Decades

A data-driven look at ridership, cost efficiency, and what happens when transit finally connects the outer boroughs to each other

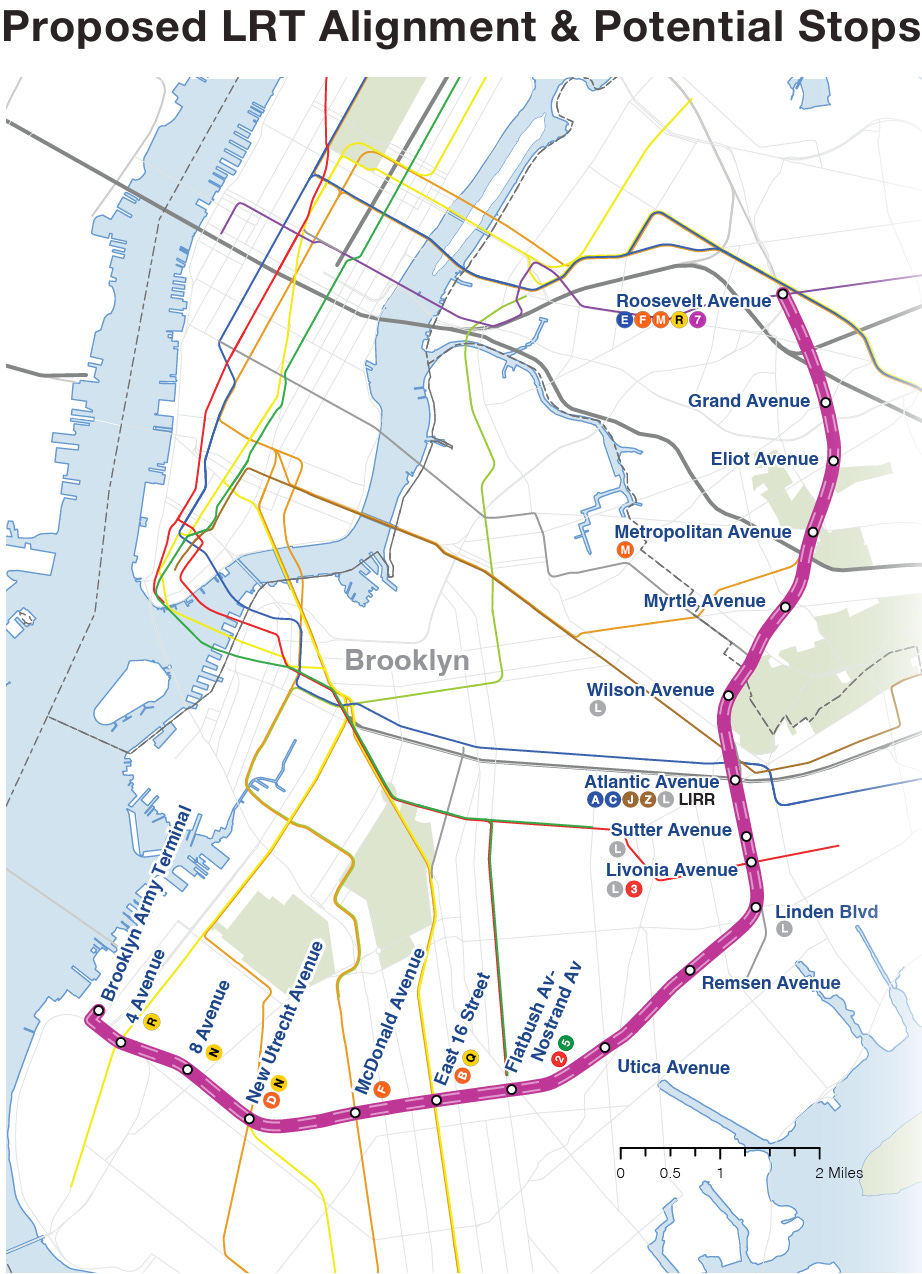

The Interborough Express (IBX) could be one of the most impactful transportation projects in NYC of the past several decades. The first new subway line, rather than an extension of an existing line, since the 1930s. The only line, besides the G, that would not connect to Manhattan, but would rather serve Brooklyn-Queens commuters.

Further, the IBX holds massive transformative potential for these two boroughs due to its location on a freight line through many low-density neighborhoods of the outer boroughs. The new subway line would not only increase connections between Brooklyn and Queens commuters and to Manhattan (through the seventeen transfers along the proposed route), but could catalyze new housing developments and businesses along the entire corridor. With impressive population growth and economic development already occurring in surrounding neighborhoods, the IBX may one day be looked on as the heartbeat of a new business district.

In this post, I will examine the facts around the IBX proposal (ground is not expected to break on the project until 2028 at the earliest) and compare it to other major transportation projects in development or recently completed in NYC.

Along the way, I will dig into the reports outlining the IBX to explain why certain decisions were made about its structure, shape, and location. I will also compare the proposed IBX light rail line to existing subway lines in the MTA system. This will allow us to place the IBX against similar transit developments and compare its impact along metrics like ridership, cost, and economic benefits.

The Key Decisions Shaping the IBX

Why light rail:

The IBX was first proposed in the 1990s, and the exact contours of what it would look like have shifted in the intervening period. In the MTA’s EIS report, it narrowed the shortlist of transit options considered to the three with the highest potential: Light Rail Transit (LRT), Commuter Rail (CR), and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT).

Significantly, NYC currently has no active LRT lines. To see one in action, residents would have to travel across the Hudson River and take the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail or Newark Light Rail, both in New Jersey. Meanwhile, CR is represented by the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North Railroad, and a version of BRT can be seen all around the City in the form of the Select Bus Service (SBS).1 So why did the MTA choose a mode of transportation entirely unseen anywhere else in the City?

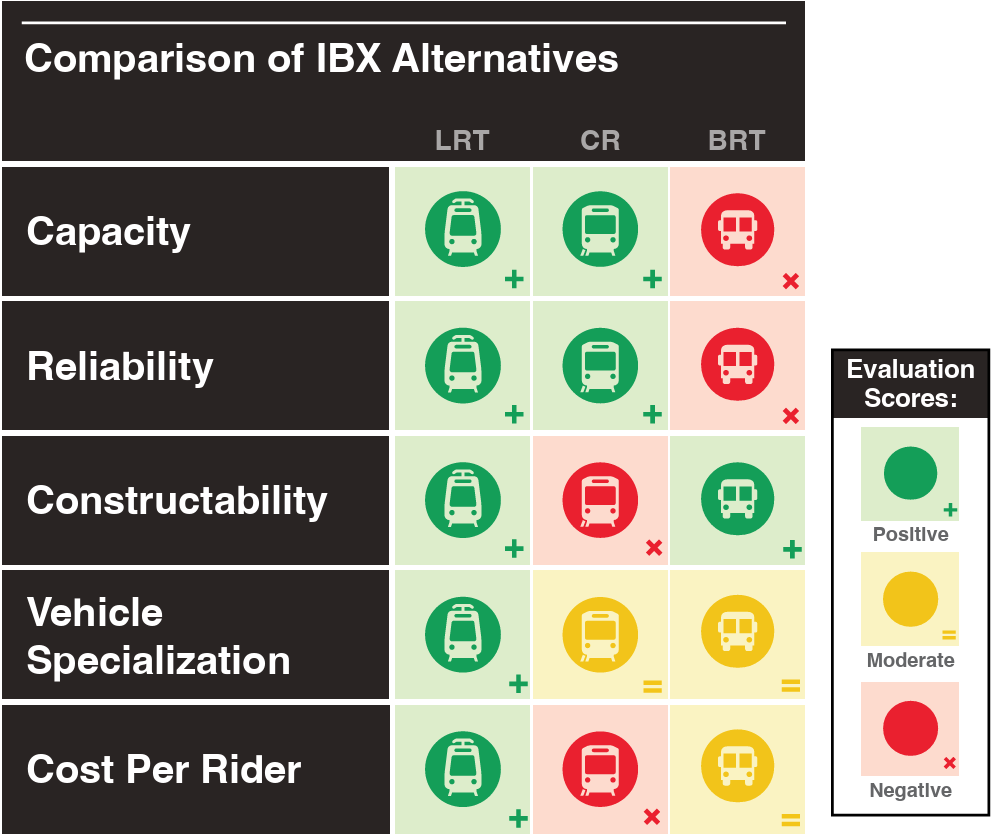

The following factors were identified as the key differentiators between the three alternatives:

Meets Forecasted Demand

Provides Reliable Service

Relative Construction Risk

Vehicle Specialization (Operational and Fleet Requirements)

Relative Cost (Cost-Effective Transit Service Improvements)

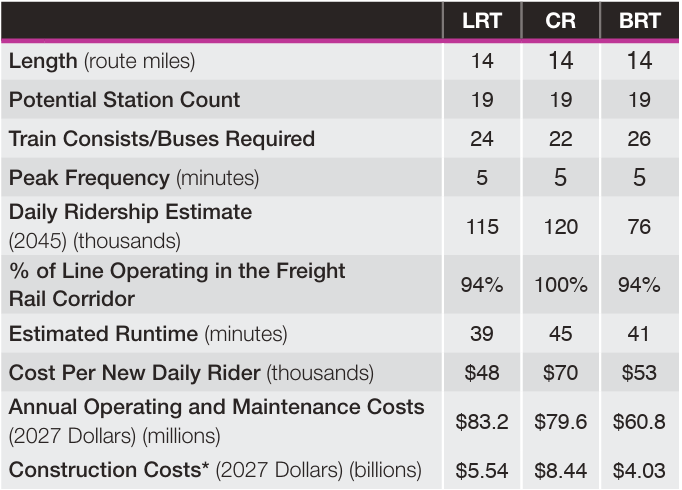

The MTA states that LRT was the only option considered that satisfied each of these factors.2 According to the report, “Thanks to its high ridership ([160,000] projected weekday riders) and relatively low construction cost ($5.5B in 2027 $), Light Rail offers the best value, with a cost of [$34,375] per daily rider. Conventional Rail had a much higher construction cost and bus rapid transit could not move as many riders.”3

Commuter Rail would require too many modifications and major redevelopments of the corridor. Buses would be too slow competing with other traffic and encounter problematic right-of-way concerns when they would have to turn around at one end of the line, at Jackson Ave. While significant redevelopment will be needed across the corridor to install new train tracks and renovate tunnels and bridges for LRT, these costs are relatively minor and pale in comparison to the benefits of a below-grade light rail train.

There were many other, nuanced factors for choosing LRT as well. Evading costly construction of new tunnels, avoiding at-grade crossings with vehicular traffic, and complying with federal laws regarding the operation of a commuter line adjacent to a freight line. But the big picture is that the LRT could move the most people, at the highest frequency, for the lowest cost.

Why this location:

The short answer is that train tracks already exist along the proposed IBX route, so developing a new commuter corridor and acquiring right-of-way here would be minimally difficult. Most of NYC is already highly developed, so any location not requiring destroying existing buildings or shutting down major roads is at a huge advantage. But the location of the freight tracks posed several other key benefits too.

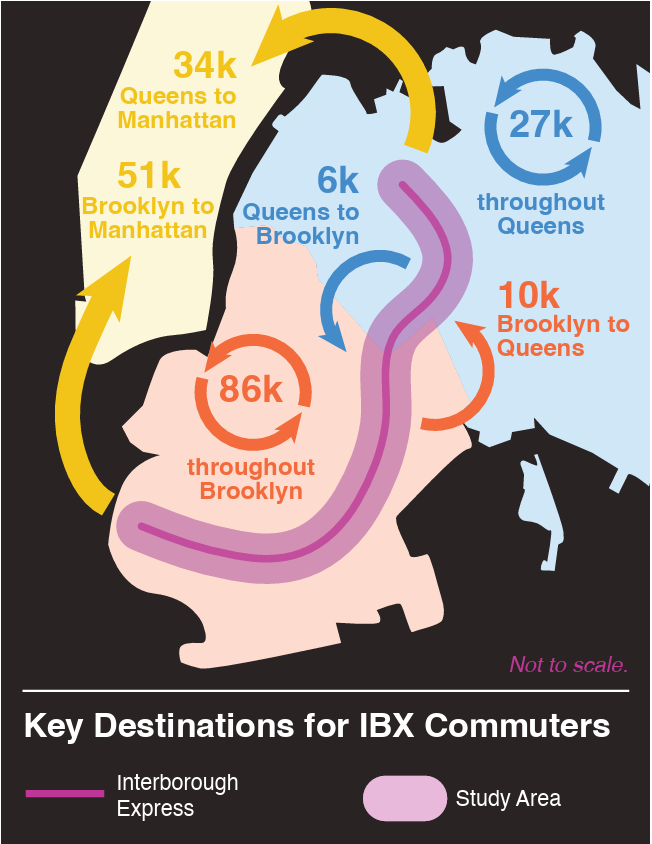

As the IBX report states, “With the exception of the G Crosstown subway line, New York City lacks high-frequency transit that connects the outer boroughs. This often results in difficult and circuitous trips from one outer borough to another.” Brooklyn and Queens have developed into major population and economic centers of their own in the decades since the subway’s original construction. Yet it remains served by a subway system focused on getting riders to and from Manhattan and a less-than-stellar bus network. A new transit option, not centered around service to Manhattan, would save riders in these two populous boroughs hours of time in their commutes.

Why now:

The MTA, in its capital projects planning, must meet the forecasted demand of transit riders through 2045. To serve the expected increase in subway ridership in NYC, particularly in Brooklyn and Queens, more stations and better service is necessary.

Thanks to congestion pricing revenue and renewed commitment to public transit by the Governor, NYC is currently enjoying a surge in transportation projects. State leadership is taking advantage of the additional revenue to develop long overdue transit routes. The IBX is not a new idea, with various proposals having bounced for it for decades. But only now do we see both the capability and the willingness by the State and the MTA to make it happen.

Okay, so that’s the background on the IBX and the context for its chosen structure (LRT), route (the freight tracks crossing through Brooklyn and Queens), and expected costs ($5.5 billion). But how does all this compare to other NYC transportation projects? And how impactful will the IBX be for NYC, really?

Estimated Impacts of the IBX

The IBX planning study found that along the 14-mile freight corridor that goes through Brooklyn and Queens is a surrounding area home to 900,000 people and 260,000 jobs. The report states that, “If built, the IBX would see higher daily ridership than nearly any new transit line built in the U.S. over the last two decades.”

Let’s compare the potential ridership and time-saved impacts of the IBX compared to other major transportation projects underway or proposed in NYC:

The IBX project is most notable in its relatively lower total cost and its low cost-per-rider potential. While the total riders served may be higher with projects like the Second Avenue Subway and the Gateway Hudson Tunnel Project, the value of the IBX makes it compelling. Thanks to the existing freight corridor and design choices to avoid costly tunneling, this entirely new commuter train line could be delivered at half the cost of the East Side Access project, which only added one new station (though it did achieve many other transit improvements).

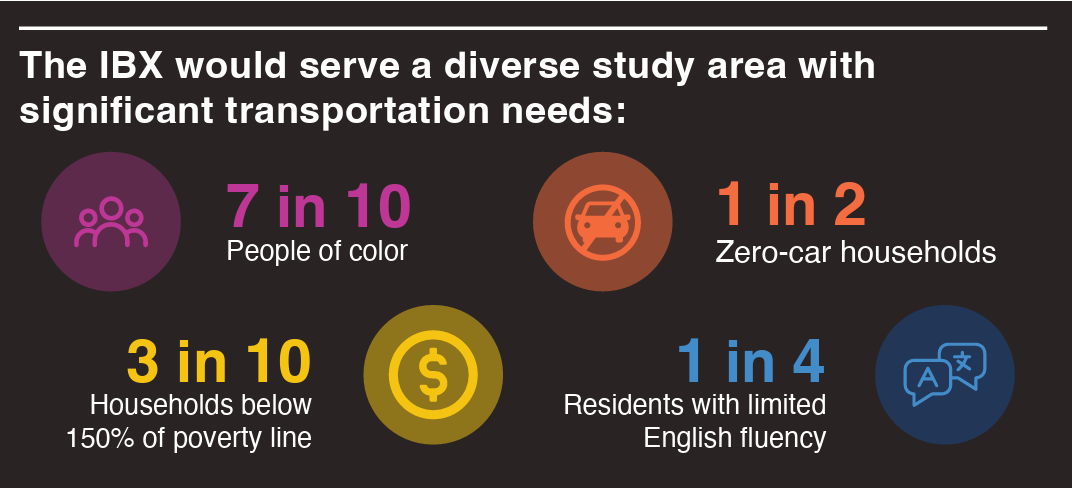

The IBX is also differentiated in its service focusing on Brooklyn-Queens connections, while every other major transportation project is building to improve connection to Manhattan. This would mean improving transit access for residents of largely lower-income, immigrant, and minority backgrounds. The MTA’s report also found that half of residents living in the area along the corridor did not own cars.

Another comparison we can make is between the IBX and some of NYC’s subway lines.4 While the IBX will be a light rail and these subway lines are commuter rail (meaning that the current subway trains have much higher carrying capacity per train than the IBX will have), they are functionally serving the same purpose: moving people around and between the five boroughs. Thus comparing the IBX to subway lines may be more relevant than to the above transportation projects, which include renovations and tunnel constructions on top of extending train lines.

Note: Peak headways are from https://pedestrianobservations.com/2015/12/13/new-yorks-subway-frequency-guidelines-are-the-wrong-approach/

For this table, I chose several subway lines that would intersect with the IBX in Queens or Brooklyn. The G shares the most characteristics with the IBX, itself being a train that only runs through Brooklyn and Queens - and we can see in the table that the G subsequently has similar daily ridership to the IBX’s projections. Another train that runs through Queens, the M, may actually have lower ridership than the IBX.

Other subway lines, like the L and the 7, had double or triple the IBX’s projected ridership in 2025 while also having more stations and higher rider capacity per train. Still, the IBX remains competitive with these lines on the number of transfers to other trains and to buses.

This could mean that the IBX, while not initially serving as many passengers as their sole ride on the commute, will be integral in providing connections to other key trains traveling to other parts of the city. While ridership may not compete with the likes of the A train (itself being one of the most ridden trains throughout the entire system), this new train can be a critical connector in neighborhoods lacking sufficient transit access today.

Conclusion

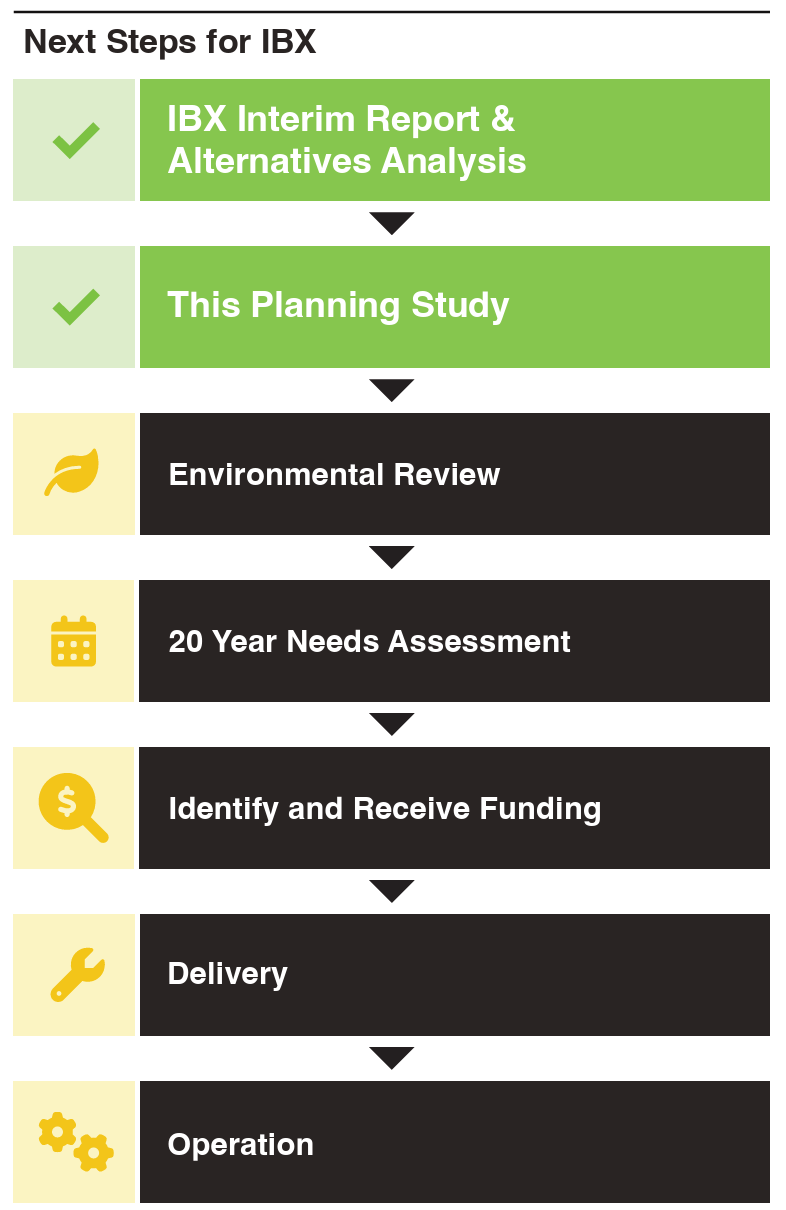

Unfortunately, the actual opening and operation of the IBX line is still many years away. It will take continued commitment from State and City leaders, combined with study funding for the MTA, to reach the finish line on this major transportation project.

The good news is that such a project was proposed in the first place and is now proceeding through the required planning steps. By all metrics, the IBX is an ambitious and rarely seen project in NYC in the 21st century. For the City to continue to succeed, more infrastructure development on this scale - and larger - will be necessary. This includes additional new transit lines like this proposed in the A Better Billion report. It also includes large-scale new development in the energy and housing sector, which will involve complex planning processes of their own.

But the IBX is a step in the right direction and an encouraging sign of growing momentum in expanding NYC’s transportation network. The MTA and transit workers will gain valuable experience in this project that can be carried to other major projects. Success on this proposal can open the door to increased funding for further proposals. And the residents of Brooklyn and Queens will receive new and better transit options to commute between their boroughs and neighborhoods in between.

I say close relation of BRT because the SBS is not exactly bus rapid transit. It lacks several of the features of BRT, such as off-board fare collection, while containing many of the other elements, such as limited-stops and dedicated bus lanes (sometimes).

“While CR would also meet the project purpose and need, it would require a new tunnel under All Faiths Cemetery. The need for this new tunnel would add construction and maintenance complexity to the project, and substantially increase the capital cost without providing significantly greater benefit to the public.”

As a result of some changes to the proposal since the initial EIS report, expected weekday ridership has increased from 115,000 to 160,000. This has brought down the cost per rider from the report’s initial estimate of $48,000. I have updated this quote with the more recent figures.

Unfortunately, the MTA does not actually provide public ridership data by subway line. Fortunately, Greg Feliu has done some amazing data work to construct rough estimates of daily ridership by train using MTA’s data on ridership by station. Check out his excellent Medium article for more information on the methodology.

Good write up! Though I think the LRT decision is *very* tied into avoiding the TWU (and that’s the best reason I’ve heard)